Brain-Machine Interfaces

Info.

Sep. 2020 ~ Apr. 2021 at Global AI Center with 4 members.

Goal

The goal of this project was to develop a Brain-Machine Interface prototype for proof-of-concept using EEG or EMG to sense, interpret, and recognize specific linguistic imagery or body movements, enabling device control based on neural signals for the exploration and validation of future interfaces.

Need

Various wearable devices, including smart watches and smart glasses, are gradually emerging in the market. Furthermore, AI-powered services have evolved from AI speakers to recent forms like LLM, expanding their influence. Consequently, there is an increasing demand for multimodal interactions that integrate text, speech, images, and more. This trend underscores the growing importance of exploring innovative methods for controlling existing mobile devices and confirming the potential for more convenient, as well as task-optimized, interaction techniques. This development aligns with the broader context of my research portfolio, reflecting my engagement with cutting-edge technological advancements and their real-world implications.

In connection with this, as I investigated relevant trends, I found that some major IT companies, such as Apple, Meta and Microsoft, were actively researching new interface technologies. Additionally, there were ongoing studies related to interpreting biometric signals like brainwaves. For our innovative project at the AI Center and as part of our exploration into future interfaces, we chose the Brain-Machine Interface as the subject. Initially, our research focused on the interpretation and recognition of speech imagery based on electroencephalography(EEG) signals.

Approach & Insights

Approach — Binary Brain-state Classifier using EEG

Leveraging our team’s expertise and experience in developing voice-based interfaces such as speech recognition and synthesis, we embarked on the project known as the ‘Mind Reading User Interface’. In this project, we aimed to achieve the ideal target of implementing mind-based wake-up functionality for AI agents, which could be realized with Speech Imagery. Considering the typical design of AR glasses and VR headsets, which encompass the front and sides of the head with a band, we envisioned that future products of these types would provide ample space for attaching sensors. While, at the time, companies like Neuralink were actively developing invasive BCIs, we aimed for a more accessible, non-invasive solution.

I was responsible for researching the project’s relevant trends and implementing the prototype using an open-source platform. This led me to explore topics such as Brain-Machine Interfaces and detailed research methodologies. As I delved into the literature, including various papers and survey articles, I gained a comprehensive understanding of EEG signal characteristics, measurement protocols, preprocessing techniques, and analytical methodologies. Sharing and discussing these insights during seminars played a crucial role in shaping our focused research direction.

Through this journey, it became evident that the typical number of sensors used in research (ranging from 30 to 120) greatly exceeded the number of sensors practically applicable in a product (around 8 to 20). From an industry research perspective, we pondered strategies to bridge this gap in sensing capabilities. However, before transitioning to speech imagery, we opted to conduct initial tests to assess whether a prototype employing practical sensors could effectively classify EEG signals to some extent.

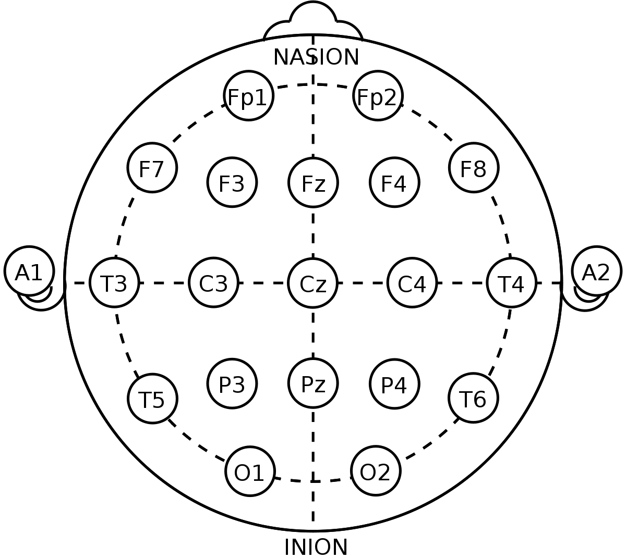

International 10-20 system for EEG signal

We set out with the primary goal of developing a binary brain-state classifier through real-time EEG measurements. Here are the steps we followed:

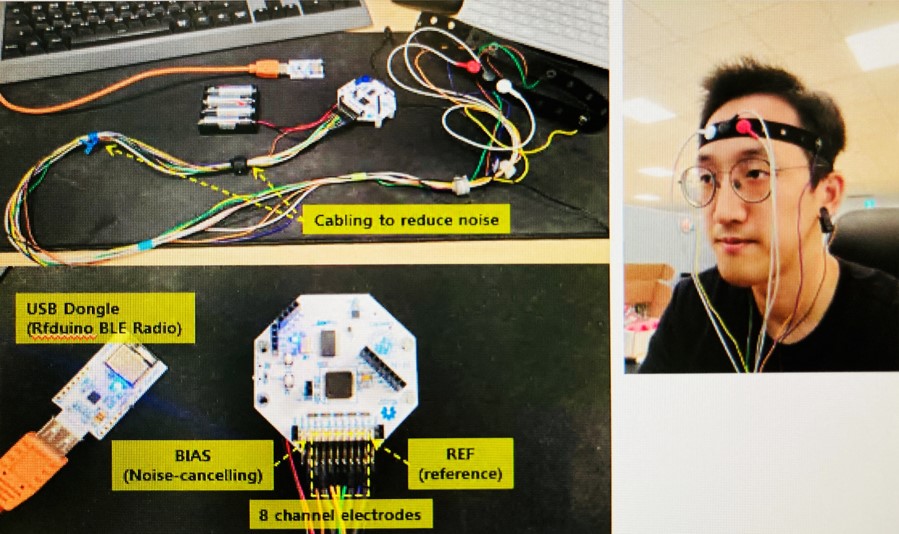

- Set-up with OpenBCI opensource biosensing hardware (ADC board & dry electrodes)

- We captured raw 8 Channel EEG signals from various brain regions (Fp1, Fp2, F7, F8, T3, T4, T5, T6) according to international 10-20 system with EEG electrodes that are placed on the scalp.

- We preprocessed the signals with edge sample reduction, z-score normalization and band-pass filtering.

- We visualized FFT spectrum, band power, head power plotting.

- Development of data acquisition tool based on a protocol that we defined.

- Comparison of time-series EEG wavelets of brain states (concentration, chilling-out)

- EEG signal indicates that different regions of brain are activated based on frequency bands and spatial Power Spectrum Density (PSD).

- ‘Concentration’ means thinking a specific word in one’s head, while ‘chilling-out’ means zoning out and not thinking about anything.

- Feature extraction by training of AutoEncoder to learn efficient data coding in an unsupervised manner

- Training the network to reduce signal noise caused by artifacts like eye blinking and mascular movement with dimension reduction

- Training classifier based on K-means clustering, and then verifying the classifier for labeled data

- Performance evaluation with validation data collected from in-house testers

Set-up with OpenBCI

Insights — Binary Brain-state Classifier using EEG

As expected from the outset, this project was quite challenging, and it proved to be difficult to achieve meaningful classification performance through evaluations and demonstrations.

Sensor Issue

In an attempt to overcome the contact noise of dry electrodes, we also tried gel-type electrodes. However, the influence of very weak signals and the significant noise interference turned out to be a challenging problem to overcome, even with the use of autoencoders for latent space representation.Calibration Issue

We anticipated that there would be consistent patterns in brainwave activity when individuals made specific visual or linguistic mental efforts, regardless of the user. This is closely related to the sensor issue, but the characteristics of scalp contact varied depending on users’ physical differences. Additionally, even though we guided users to minimize physical movements during the experiments, there was still a significant variation in the impact of artifacts. Consequently, calibrating the pure brainwave differences remained a real challenge, and obtaining pure brainwave data for individual users proved to be a formidable task in itself.

In conclusion, we came to realize that there are substantial limitations in detecting meaningful differences in signal interpretation under constraints related to sensor types and quantities, targeting a specific device. After multiple validations and demonstrations, we acknowledged the considerable gap between reality and our ideals. Following the advice of our director, Prof. Daniel D. Lee, we decided to pivot our focus towards a more pragmatic direction.

Approach — Hand Gesture Recognition using EMG

Following the process outlined earlier, we revised our objective to develop a wristband-shaped prototype capable of recognizing hand gestures through EMG signals. Drawing inspiration from CTRL-Labs, a neural interface startup, and their Ctrl-kit, our goal was to assess the feasibility of a solution that could be integrated into the band of wearable devices such as the Galaxy Watch. Despite not achieving an integrated design with on-chip sensors similar to the wristband introduced by Reality Labs after Meta acquired Ctrl-labs, we developed a wristband prototype outfitted with metallic electrode sensors. This prototype, using Bitalino—an open-source biosignals platform—was engineered to classify and recognize fundamental hand gestures such as Rock, Paper, Scissors.

During my involvement in the research project on EMG signals, I unexpectedly came across a job posting for the Robot Center. Fueled by my passion for robotics research, I decided to seize the opportunity to transfer to the new department, leaving my regrets behind.