Neural Speech Synthesis

Info.

Apr. 2018 ~ Jan. 2020 at Language & Voice Team with 10 members

(4 members in overseas research institute).

Goal

The aim of this project was to develop a commercially viable and efficient deep learning-based speech synthesis model.

Need

During a period when entertaining demonstrations mimicking celebrities’ voices using deep learning-based open-source tools were on the rise, we aimed to replace our already commercialized parametric Text-To-Speech model with a high-quality yet lightweight Neural Speech Synthesis solution. This new solution needed to be capable of serving as an AI voice synthesis engine for Bixby.

Approach

Before moving towards a complete end-to-end model, we conducted research by incrementally developing a neural speech synthesis model that combined an Acoustic Model based on Tacotron[1] or DC-TTS[2] with a Vocoder Model like WaveNet[3], Parallel WaveNet[4], WaveRNN[5], or LPCNet[6].

The acoustic model takes sequential texts as inputs and produces the inferred mel spectrogram using an attention-based seq2seq model. Subsequently, the vocoder model takes the mel spectrogram and converts it into speech data using a probabilistic generative model.

Let’s briefly take a look at the models related to the vocoder that I have been involved in developing.

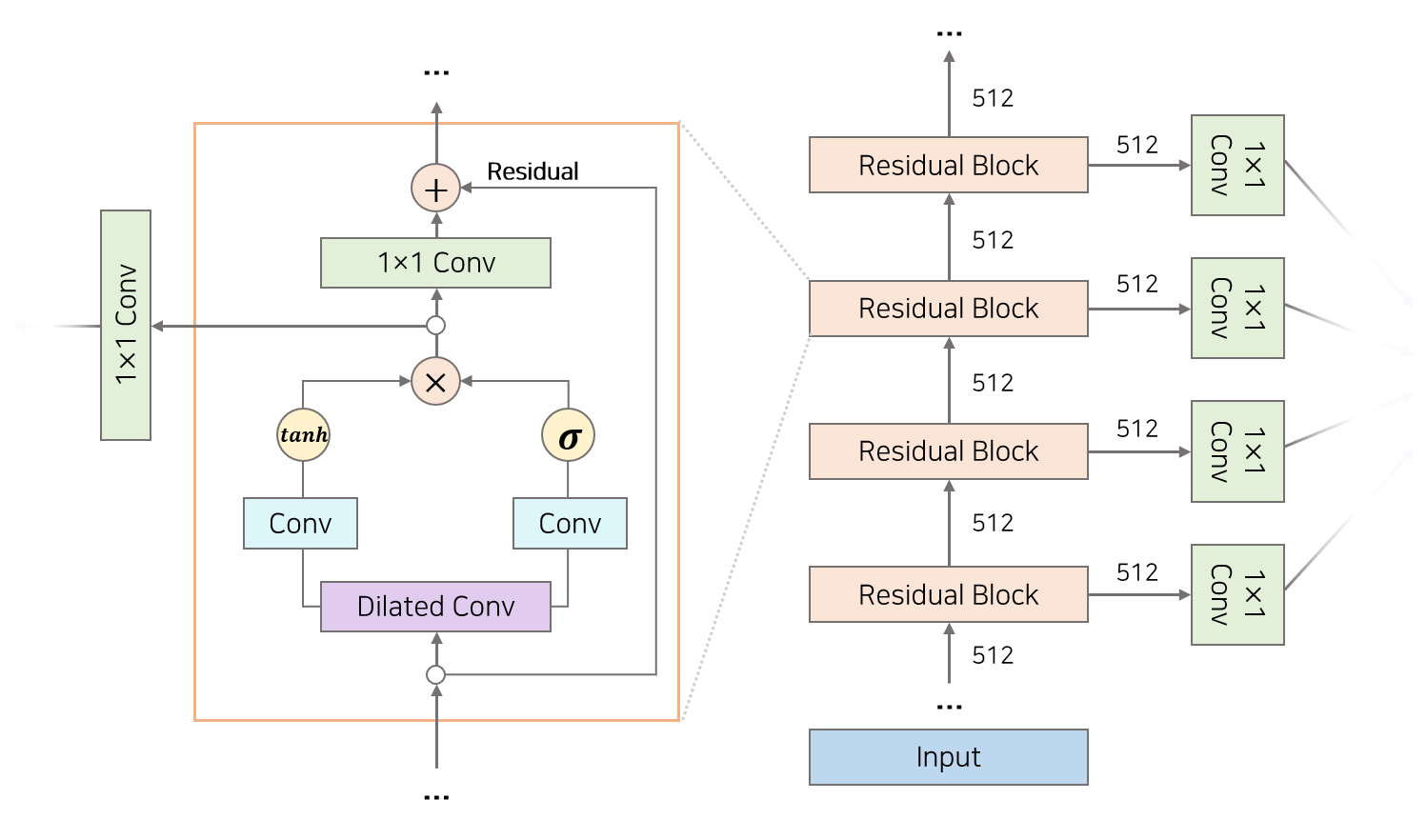

WaveNet models the conditional probability of each input audio data within a specific range of receptive fields up to the current time step to predict the next audio data point. To generate the original 16-bit audio data while simplifying the process, it employs an 8-bit μ-law companding algorithm. This algorithm predicts a categorical distribution by considering the probabilities for each integer in the range of -127 to 128. The model consists of a chain of residual blocks including dilated causal convolution layers and gated activation units, which makes it possess the characteristics of an autoregressive model.

Residual blocks

Dilated Causal Convolution layers

WaveNet was capable of generating high-quality speech, but due to its sequential inference process, it had a slow generation speed compared to parallel processing in training, which limited its real-time applications.

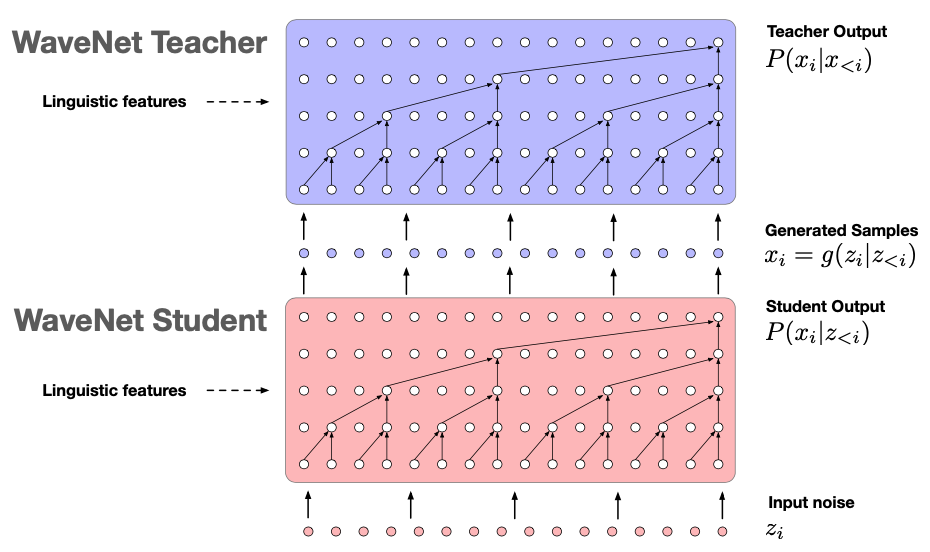

Parallel WaveNet is a model that combines the advantages of WaveNet, which can be trained in parallel as an Autoregressive Flow (AF), and Inverse-Autoregressive Flows (IAF), which can be inferred in parallel, to accelerate the overall audio sample generation process. To achieve this, WaveNet is used as a teacher network, and Parallel WaveNet is used as a student network. The teacher network with an AF structure is trained, and this teacher network is used to train the student network with an IAF structure through Probability Density Distillation[7]. During the distillation process, loss is defined using KL divergence to make the distributions of the teacher and student networks similar. Through this method, the student network learns how to sample from noise, enabling it to generate audio data more than 20 times faster than WaveNet, making real-time applications feasible.

Parallel WaveNet

While Parallel WaveNet has overcome the slow generation process of WaveNet, the need to train two separate models makes it a cumbersome learning process with a relatively high computational complexity, posing challenges in deployment.

LPCNet is a model that, as the name suggests, combines traditional Linear Predictive Coding (LPC) with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and is an evolution of the WaveRNN model. It offers higher audio synthesis quality compared to WaveRNN and is deployable on low-power devices with a low complexity of around 3 GFLOPS. This efficiency is achieved by implementing spectral envelope modeling without using neural networks. This is noteworthy because it offloads the task of simulating filtering within the vocal tract, which can be challenging for neural networks, to digital signal processing algorithms.

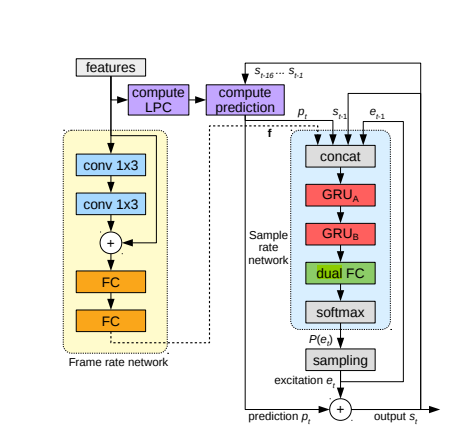

In the diagram below, it consists of a sample rate network operating at 16kHz and a frame rate network that applies a conditioning vector every frame at 100Hz. It takes an input of 20 features, which is a combination of 18 Bark-scale cepstral coefficients and 2 pitch parameters (period, correlation). The LPC block is used to calculate prediction coefficients from these features, and the filter block labeled as “compute prediction” calculates predictions from past samples and the coefficients computed by the LPC block. Then, the network is trained to predict the difference between the next sample and the prediction.

LPCNet Structure

Based on this structure, LPCNet demonstrated good performance in subjective quality tests compared to WaveRNN+. It was also able to reduce complexity to a level that could run on a single smartphone core.

Outcome

After conducting extensive research and analyzing various models over an extended period, we implemented and optimized our proprietary Neural Vocoder model based on LPCNet at the time. Through this process, we were able to commercialize an on-device AI voice synthesizer targeting mobile devices.

The content introduced above is simply a conceptual explanation aimed at giving a rough overview of what the project entailed. However, going along with the evolution of speech synthesis models and understanding the characteristics of each algorithm was indeed a valuable experience. Additionally, conducting hyperparameter tuning to improve performance, experimenting with various datasets to achieve more generalized models, and making adjustments to local conditioning were some of the methods employed to train deep neural networks in different ways, resulting in gaining many insights into deep learning research.

Insights

- From Vocoder Development to Multifaceted Aspects of Deep Learning Model Deployment

The central focus of my work was the development of the vocoder model. However, due to our team’s limited size, I had the unique opportunity to gain experience in every aspect of deploying deep learning models. This encompassed a wide range of tasks, from data preprocessing to model evaluation through both internal and external online channels, as well as optimization efforts essential for commercialization through collaborative efforts. These tasks included:- Dataset creation through automated data refinement and preprocessing procedures.

- Management of databases organized by language, speaker and audio quality.

- Development and execution of speaker-specific model training plans to achieve the desired speech synthesis model.

- Experimental comparison of model performance based on various parameter combinations.

- Evaluation of the Korean model using in-house online assessment tools.

- Evaluation of the English model targeting native speakers using AWS.

- Porting of Python code to C code and optimization efforts involving application of intrinsics functions.

Experiments on Local Conditions in the WaveNet Model & Challenges of Generalizing across Diverse Speakers

When I initially embarked on this project, I was relatively inexperienced in the field of AI, and I wasn’t familiar with the implementation of complex deep learning models. My knowledge of speech signal processing was also limited, which hindered my direct contribution to coding. However, through reviewing the code for various components of the model and experimenting by modifying detailed structures and parameters, I gained a substantial understanding of model implementation and development as a whole.Throughout extensive discussions with my colleagues, I planned and executed various experiments. One of these experiments aimed to apply local conditions to the WaveNet model using speaker-specific embedding vectors to obtain a universal model. Data from numerous speakers was segmented into groups based on characteristics like gender, language, and audio quality. Subsequently, embedding feature vectors were incorporated as local conditions, and group-specific models were trained. The performance of these models was then compared with that of individual speaker-specific models.

While some models grouped by similar characteristics exhibited performance resembling that of individual speaker models, they fell short in terms of clarity. Additionally, both the universal model trained on data from all speakers and models fine-tuned through approaches like few-shot learning using this pretrained model failed to deliver satisfactory results. I had hoped to achieve a harmonious conclusion where multiple speakers’ voices could be synthesized by a single model as I read in the literature, but confirming strong local conditioning performance proved elusive.

Due to various ongoing tasks, I couldn’t delve deeply into this issue, but I’ve come to believe that achieving a generalized model for complex inference problems, akin to the recently acclaimed foundation models, likely necessitates a vast amount of high-quality data on the order of billions. Of course, it may not need up to a billion units for speech synthesis problems. Nevertheless, given the opportunity, I would like to explore whether it's possible to obtain such a model for various tasks within the same domain, even though they possess distinct characteristics.

Synergy between Classical Domain Knowledge and Deep Learning Models

While developing deep learning models, one thing we discussed a lot with our team members was that “ultimately, knowledge of the domain you want to apply AI technology to is key.”LPCNet, as described above, demonstrates how it efficiently incorporates Linear Prediction Coding (LPC), a technique traditionally used in speech processing to model the frequency characteristics of speech signals, into a deep learning model. Because it offers a good balance between quality and efficiency, making it more suitable for real-time scenarios where low latency is crucial.

Therefore, I believe that such synergy can exist sufficiently in various fields of robotics, including visual navigation. While the learning algorithms and mechanisms are essential themselves, I think that in applied and empirical research areas like robotics, the practical impact often depends on how deep learning theories are implemented in conjunction with domain knowledge.

Furthermore, the reason I believe there may be even more potential in this research direction, particularly in robotics, is because the problems are inherently more complex and on a larger scale. Additionally, recent trends in multimodal learning have become increasingly diverse. Whether the data used in target scenarios is language, speech, or visual data, exploring how humans interact using multiple senses and conducting research to enable artificial intelligence to integrate and learn from various data sources is crucial. I find this process extremely fascinating.

References

[1] Wang, Yuxuan, et al. “Tacotron: Towards End-to-End Speech Synthesis.” Interspeech 2017 (2017).

[2] Tachibana, Hideyuki, Katsuya Uenoyama, and Shunsuke Aihara. “Efficiently trainable text-to-speech system based on deep convolutional networks with guided attention.” 2018 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2018.

[3] Oord, Aaron van den, et al. “Wavenet: A generative model for raw audio.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.03499 (2016).

[4] Oord, Aaron, et al. “Parallel wavenet: Fast high-fidelity speech synthesis.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018.

[5] Kalchbrenner, Nal, et al. “Efficient neural audio synthesis.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2018.

[6] Valin, Jean-Marc, and Jan Skoglund. “LPCNet: Improving neural speech synthesis through linear prediction.” ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2019.

[7] Hinton, Geoffrey, Oriol Vinyals, and Jeff Dean. “Distilling the knowledge in a neural network.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.02531 (2015).

I became interested in pursuing a career as a researcher while working on the speech synthesis project. Furthermore, through collaborating on AI voice support for robots, I have continued to nurture the desire I had when working on TV system development – the exploration of dynamic systems. These thoughts have become intertwined with my passion for self-maintenance and track driving, combined with my love for cars, which has further fueled my strong desire for research in robotics and autonomous driving. So, in response to the request for resources to develop a multimodal interaction framework for “robots” and AR/VR, I decided to move to the AI Center with the hope of making a meaningful contribution to the robot system…